In the age of chivalry, when knights donned skins of

shining armor, they hoped to metamorphose

mortal flesh into gleaming beacons of courage and honor. When battlefields sparked

with the glint of sunrays reflected on mirror polished steel,

the conflict between good and evil transformed into a battle of light.

Yet, mirror polished plate

often created only an illusion of strength where there was weakness.

In the age of chivalry, when knights donned skins of

shining armor, they hoped to metamorphose

mortal flesh into gleaming beacons of courage and honor. When battlefields sparked

with the glint of sunrays reflected on mirror polished steel,

the conflict between good and evil transformed into a battle of light.

Yet, mirror polished plate

often created only an illusion of strength where there was weakness.

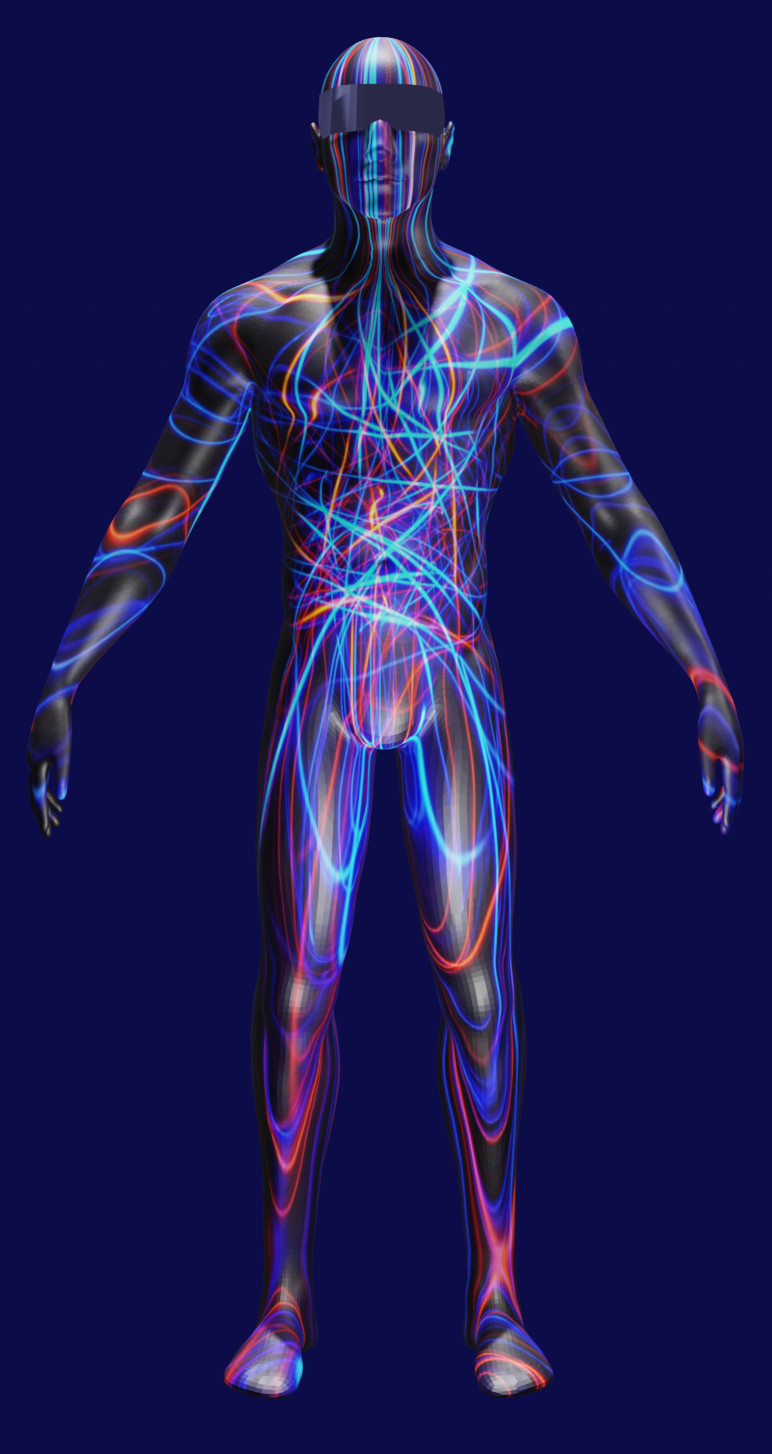

I was about to don my own lightsuit, but whether it would infuse courage and honor in me or only mask my weakness was to be seen. Kevin Armstrong came by my house on Thursday at 7:00 AM prompt to pick up Emma and me for a full day at the bioengineering lab. "This is quite a day ," Armstrong admitted as he drove down the winding road from the Los Altos hills towards the University campus and the biomedical engineering facility. "For the first time we have a chance to demonstrate a fiber-optic neuro-net that's better than just a crude prototype." "You're not half as excited as I am," I called from the back of the van, stuck in my wheelchair with Emma riding shotgun. "Riding in the back of the bus isn't my idea of fun!" Armstrong caught the double meaning of my status as second class citizen. "A lot of handicapped people will benefit from this project too, even if it is funded by the Department of Defense. Steve, we couldn't do this without you, you're a genius when it comes to control software." "I sure hope we can help a lot of other people by making this work." I responded conscientiously. But my motives weren't all that pure. I was more concerned with saving my own hide from a fate worse than death - becoming a mere quadriplegic passenger on life's rollercoaster held no appeal for me. Perhaps it should have struck me that there were other reason for pursuing this besides my own selfish needs. I'd heard the line that millions of others were suffering similar injuries and needed my help. But truth be told, being able to walk beside Laura Silvan was what really possessed me, those millions could write their own damn software. "Time to get to work," Andy greeted me as I was lowered in my wheelchair off the van. "Eric's got a fine suit tailor made for you!" This was the first time I'd been in the bioengineering facility. It was bright and cheerful, not like the clinical medical facilities with their antiseptic linoleum. "Come down to our la-bor-a-tory," Andy pronounced theatrically as he led me down a corridor of offices interspersed with larger work rooms. You could see electronics racks and biomedical rigs through the glass work room observation windows and occasionally some patients exercising or being examined. "Like monkeys in a zoo," I muttered, but Andy overheard me. "Boy, you've got a chip on your shoulder! The people here are the lucky ones who can make a difference in medical technology." "Maybe there there is a career waiting for me as a medical guinea pig. . ." I began to respond, but came up short.

"Pretty outrageous, huh!" Eric beamed at his creation. "I call it a lightsuit, it glows in the dark!" "It's nothing like I thought," I marveled out loud. Even Emma, the stodgy German plowhorse nurse was impressed enough to grunt in approval. "Ja, dat's pretty!" "The best way to see how your fiber optic suit will work is by turning off the lights and turning the suit on," Kevin suggested as he hit the wall light. Eric already had the computer booted up and linked to the lightsuit so he simply clicked on the start() command and the most eerie of effects became apparent. "God, the whole thing glows and sparkles like little stars," I raved. "This thing is beautiful!" It's strange, but sometimes the most beautiful designs come not from artists dedicated to producing startling effects, but from scientists and engineers in pursuit of the mundane and practical. Eric had produced a lightsuit that was amazing in its shear beauty for the whole thing glowed in the dark with a rainbow of colors. But most startling was that the sensory ends of the light fibers gave off sparks of brilliance when they were accessed by the computer, making them flash like tiny stars. "Watch this," Eric exulted and as he moved the mannequins joints, ripples of color spread along the filament web indicating even to the unaided eye that motion had taken place. "Rainbowing is what you see from the outside, but the computer gets a ton of data from a movement by interpreting changes in frequency of the light. Stress in the fibers is reflected in their transmissivity, so you get the rainbow." "So what do you think, Steve," Kevin asked. "Have we made you the finest threads in America or what?" "Well, let's put it on and see if it works," I beamed. "I ordered this tuxedo months ago and it's about time you guys delivered!" After Kevin turned on the lights, it took an hour for us to put the suit on me in a meticulous process. Besides the fiber optic components of the lightsuit, there were also electrical connections that had to be made between fiber sensory endings and my skin that took time to establish. My limp body was laid out on an examination table so the engineers could work around me. Even Emma pitched in. The lightsuit was weblike, as tight as a diver's wetsuit, with only one seam running from the tip of the chin to the abdomen. It had connectors that extended to an electrical umbilical cord that carried data to the multiplexed computer. Because of its weave the lightsuit could stretch and flex, though the fibers and wiring themselves were not so flexible, sort of like the Chinese finger torture toy. I thought the suit would be claustrophobic, but it was flexible and lite enough that the feeling of being cocooned wasn't noticeable. Technically I couldn't feel anything because of my paralysis, but you still can sense these things. There was a fiber bundle that ran from the middle of the back of the lightsuit about ten feet to a multiplexed connection box. Being attached to an umbilical cable was a small thing compared to the question of whether I'd be able to move again at all, but deep inside there was the nagging question of freedom. Would I be chained to my external computer nervous system with a fiber optic cable like a dog on a leash? The first artificial heart transplant patient, Barnie Schwartz, had been a prisoner of his technology, pushing a bulky cart with his mechanical pump around and I wondered if that would be my fate? "Isn't the connector cable going to limit my mobility?" I asked Eric in passing. "Only for a couple more weeks." Eric replied. "Robby Edwards had to deal with the umbilical connection and it was a nightmare. But Bubba Graham and his artificial intelligence crew are working on a communications board for you so we can satellite-downlink control your activities through a distributed fast switching WiFi Internet connection rather than tying you to the computer direct. We'll be able to link your visor directly into the system too through your neurophotonic brain implants." "Pretty sophisticated," I confessed. "I'll be sort of an Internet cyborg!" "We're not there yet," Eric cautioned. "For right now you're still connected to a multiplexing box which is connected to the computer." Emma had brought some knitting and when we were finished putting the lightsuit on, she sat down off to the side to watch and knit. "It looks like first sweater I knit as child, not very good." She commented lumpenly. "If it works, who cares," Eric replied sarcastically. Emma got on everyone's nerves. "You won't need her, if this works," he whispered to me. "That ought to give you even more incentive to put up with the tailoring process." "Of course, we just had your rough body measurements to go by," Kevin apologized when it became clear the suit didn't fit my body perfectly. "And we need to put in a lot of connections we didn't have time to finish," Andy also apologized. "It looks and feels great to me," I commented. "I'd wear a hair suit if it would make me walk again. Let's power this thing up!" "Well, you know this is still experimental," Eric cautioned. "So we want to start slowly." "Okay, but let's get on with it," I returned impatiently. "I've got a hot date waiting." When all the connections had been made, Eric ran a large joint stimulation program for the shoulders so we could test the system out. It's a lot easier to move a large muscle group like the biceps than small ones such as those attached to the fingers, so we began working the upper body starting with the lats - latissimus dorsi - that cover the upper back. One by one, the large muscle groups responded to Eric's programming at the keyboard and we progressed through to the muscles of the torso and finally legs. "We haven't seen any problems so far," I finally became impatient. "Can't we give the whole thing a run and get on with it? You have my newest computer code, don't you?" I was damn confident in my programming abilities. "Listen, we don't know what can go wrong when you combine all these inputs," Andy tried to calm me down. "We're as excited as you are to get the whole thing up and running, but you've got to follow scientific procedure." "To hell with scientific procedure," I muttered. It was three in the afternoon before we'd gone through the entire scope of large muscle movements and into some of the minor ones. Andy had been taking readings on the sensory feedback system while Eric worked with the muscle stimulators to see they were matched up correctly. Bubba Graham stopped by. "The military people have a keen interest in seeing this work," he ignored my presence even while going on to look at the various connection details. "It bothers me that I won't have much control over the lightsuit system on a conscious level yet," I chatted as Andy and Eric continued their prep work. "The sensory inputs and dynamic control outputs are interpreted by computer algorithms rather than my thoughts, so I'm sort of a guided missile with a talking head stuck on top of it." "We'll be able to patch in a control circuit through the heads-up visor to your neurophotonic implants," Bubba interrupted me. "We can monitor the electrical nerve impulses the brain gives off and interpret them as motion commands. The air force has been working on this forever for pilots with heads-up displays." Direct neural control was the objective, but I think Eric, Kevin and Andy thought that idea was pushing the envelope pretty hard given the amount of software needed. "There are limitations to this technology," Kevin Armstrong warned me in his role as engineer/psychiatrist. "I think we can make you walk again, but it would be a stretch of the imagination to hope to see yourself ballroom dancing. The interface we can build between the computer and your mind is just too primitive to carry all of your wishes. You'll never dance like you're on reruns of Dancing With The Stars I'm afraid." Some help he was, like I'd want to dance like some dried up ex stars on the billionth episode on FederalYoutube. I had dreams for this filament nervous system we were crafting from fiber-optic fibers that didn't include clanking around like a cyborg. I wanted to figuratively fly in this new body of mine. I wanted to be free of a paralyzed prison of immobility to scale mountains, run marathons and chase my dreams. I wanted to be human again and most of all I wanted to make love to Laura Silvan. "Well, if you really want to try the whole major muscle system interface all at once, it's up to you," I was interrupted in my thoughts by Eric. "Personally, I don't think it's a good idea." "But we'll never learn without trying," Andy spoke up. I suspect he wasn't so much agreeing with me as weighing the probability of success, which I doubt he put at anything greater than 30/70. "I'm ready, the system is ready, let's do it!" I wasn't thinking rationally, it was pure pent up emotions. Word went out through the building that we were going to try and make history, so Kevin came back in to observe, as did some of the workers and researchers from up the hall. Even the janitor came by, it was a small family here and they knew how much work had been put into this. "All right, we're going to try to make you sit up," Eric finally signaled he was ready. "Andy worked hard on this algorithm, plotting the dynamics of sitting, but there's still a lot that can go wrong. I'll count to three so you can get ready and then I'll hit the enter key to activate the sequence. There was so little I could do to get ready, I didn't have the slightest control over three quarters of my body. Even a pupae in a cocoon can wiggle about in a limited way, but without the activation of the light filaments, I was a quivering slab of Jell-O. "Three.-- Two.-- One." The room counted in hushed tones with Eric. The process of sitting up from a flat position is something normal people take for granted, it's how you get out of bed in the morning. But when you analyze the dynamics of sitting up, or of any other human body motion, you soon discover just how complex the control machinery that makes animals function truly is. Under computer control, my stomach muscles began to tense and my arms at my sides began to push down at the elbows. Unfortunately, my neck muscles which were under my own mental control were not in sync with the motion and caused me to arch my head backward further than necessary, and the software compensated. The abductors in my legs kicked in to rotate my pelvis to counter the torque from the stomach muscles and I began to sit up in a rather jerky motion to the encouragement of the observers in the room. "Come on Steve! You can do it!" Andy urged me on, but my body was starting to tremble in surges, wavering ever so slightly up and down. "Cut some of the gain on the feedback, Eric." Andy noted in scientific mode. But that only seemed to make things worse, and though I was now half way into a sitting position I was going into spasms. I started to shake, first in slight tremors and then more wildly, my hands drumming the table in a staccato like I was Desi Arnez doing a drum rendition of Babalu. "Hold him down, Andy," Kevin called out. I was beginning to move in a decidedly non-human way, my arms and body beginning to gyrate like an off balance washing machine. I jerked and twisted and with a spastic lunge fell off the exam table with a sickening thud before Andy or Kevin could stop me. I simply couldn't resist the spasms that now controlled me. "Shut it off, Eric," I tried to yell, except the muscles of my ribs were not in my control and were spasming, so what came out was a grotesque gagging scream. "Shit!" Eric yelled in panic. "The software loop locked! Pull the plug, Andy!" But Andy was too busy wrestling with me, trying to keep me from hurting myself as the computer threw me about the floor like a rag doll. It was Emma who came to my rescue, her German ox foot with its muscular calf came down heavy on the power strip on the floor. She broke the switch, but also cut the computer power and stopped the bizarre feedback that was contorting my body. As quickly as that, it was over and I lay there, silent but with teeth clenched tight in pain. I was bleeding where I'd gashed my forehead on an instrument rack and I was diaphragm breathing heavily, as were Kevin and Andy. The room was hushed for a long moment for this wasn't just an experimental mishap, what we'd experienced as a group was the humiliation of a human spirit. "I guess we were just trying too hard," Kevin was the first to speak. "Just pushing a little too fast." We never saw that in the simulations!" Andy added thickly. There was a tear of blinding frustration that rolled from my eye. My situation was completely hopeless. I could feel the wet drop as it slid downward and mixed with the blood on my cheek, smearing a fiber optic bundle. I hoped no one would notice it, grown men don't cry. |

Eric was waiting in one of the work rooms, standing in front

of what seemed a tailor's mannequin, except the clothes that were

being pieced to the dummy weren't anything out of the Kardashian catalogue.

Eric was waiting in one of the work rooms, standing in front

of what seemed a tailor's mannequin, except the clothes that were

being pieced to the dummy weren't anything out of the Kardashian catalogue.